Evangelical Fundamentalist Born Again Christians

Christian fundamentalism, also known every bit fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism.[1] In its modern course, it began in the belatedly 19th and early on 20th centuries among British and American Protestants[2] as a reaction to theological liberalism and cultural modernism. Fundamentalists argued that 19th-century modernist theologians had misinterpreted or rejected certain doctrines, especially biblical inerrancy, which they considered the fundamentals of the Christian faith.[iii]

Fundamentalists are almost ever described as holding to the beliefs in biblical infallibility and biblical inerrancy.[4] In keeping with traditional Christian doctrines concerning biblical interpretation, the role of Jesus in the Bible, and the role of the church in society, fundamentalists normally believe in a core of Christian beliefs which include the historical accuracy of the Bible and all of the events which are recorded in information technology as well equally the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.[v]

Fundamentalism manifests itself in various denominations which believe in various theologies, rather than a unmarried denomination or a systematic theology.[six] The ideology became active in the 1910s later the release of The Fundamentals, a twelve-volume set up of essays, apologetic and polemic, written by conservative Protestant theologians in an attempt to defend beliefs which they considered Protestant orthodoxy. The movement became more organized within U.S. Protestant churches in the 1920s, especially amongst Presbyterians, as well as Baptists and Methodists. Many churches which embraced fundamentalism adopted a militant mental attitude with regard to their core beliefs.[ii] Reformed fundamentalists lay heavy accent on historic confessions of religion, such equally the Westminster Confession of Faith, as well as uphold Princeton theology.[seven] Since 1930, many fundamentalist churches in the Baptist tradition (who generally affirm dispensationalism) have been represented by the Independent Fundamental Churches of America (renamed IFCA International in 1996), while many theologically conservative connexions in the Methodist tradition (who adhere to Wesleyan theology) align with the Interchurch Holiness Convention; in various countries, national bodies such every bit the American Council of Christian Churches exist to encourage dialogue between fundamentalist bodies of different denominational backgrounds.[viii] Other fundamentalist denominations have footling contact with other bodies.[9]

A few scholars label Catholics who reject modern Christian theology in favor of more than traditional doctrines as fundamentalists.[10]

The term is sometimes mistakenly confused with the term evangelical.[xi]

Terminology [edit]

The term "fundamentalism" entered the English linguistic communication in 1922, and it is ofttimes capitalized when information technology is used in reference to the religious movement.[i]

The term fundamentalist is controversial in the 21st century, because it connotes religious fanaticism or extremism, specially when such labeling is applied beyond the movement which coined the term and/or those who self-identify as fundamentalists today. Some who hold certain, but not all beliefs in mutual with the original fundamentalist move reject the label "fundamentalism", because they consider it as well pejorative,[12] while others consider information technology a banner of pride. Such Christians prefer to utilize the term fundamental, every bit opposed to fundamentalist (e.g., Independent Fundamental Baptist and Independent Fundamental Churches of America).[xiii] The term is sometimes confused with Christian legalism.[14] [15] In parts of the United Kingdom, using the term fundamentalist with the intent to stir up religious hatred is a violation of the Racial and Religious Hatred Act of 2006.

History [edit]

Fundamentalism draws from multiple traditions in British and American theologies during the 19th century.[16] According to authors Robert D. Woodberry and Christian Due south. Smith,

Following the Civil War, tensions developed between Northern evangelical leaders over Darwinism and higher biblical criticism; Southerners remained unified in their opposition to both. ... Modernists attempted to update Christianity to match their view of science. They denied biblical miracles and argued that God manifests himself through the social evolution of social club. Conservatives resisted these changes. These latent tensions rose to the surface after Earth War I in what came to be called the fundamentalist/modernist dissever.[17]

However, the divide does not mean that there were just two groups: modernists and fundamentalists. There were likewise people who considered themselves neo-evangelicals, separating themselves from the extreme components of fundamentalism. These neo-evangelicals also wanted to separate themselves from both the fundamentalist motility and the mainstream evangelical movement due to their anti-intellectual approaches.[17]

Fundamentalism was get-go mentioned at meetings of the Niagara Bible Conference in 1878.[18]

In 1910 and until 1915, a series of essays titled The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth was published past the Testimony Publishing Company of Chicago.[19] [20]

The Northern Presbyterian Church (now Presbyterian Church building in the United States of America) influenced the motility with the definition of the v "fundamentals" in 1910, namely biblical inerrancy, nature divine of Jesus Christ, his virgin nativity, resurrection of Christ, and his return.[21] [22]

Princeton Seminary in the 1800s

The Princeton theology, which responded to higher criticism of the Bible by developing from the 1840s to 1920 the doctrine of inerrancy, was another influence in the motility. This doctrine, as well called biblical inerrancy, stated that the Bible was divinely inspired, religiously authoritative, and without error.[23] [24] The Princeton Seminary professor of theology Charles Hodge insisted that the Bible was inerrant considering God inspired or "breathed" his exact thoughts into the biblical writers (2 Timothy iii:16). Princeton theologians believed that the Bible should be read differently than any other historical document, and they also believed that Christian modernism and liberalism led people to Hell just like non-Christian religions did.[25]

Biblical inerrancy was a particularly significant rallying point for fundamentalists.[26] This approach to the Bible is associated with conservative evangelical hermeneutical approaches to Scripture, ranging from the historical-grammatical method to biblical literalism.[27]

The Dallas Theological Seminary, founded in 1924 in Dallas, volition take a considerable influence in the move by training students who will establish various independent Bible Colleges and fundamentalist churches in the southern U.s..[28]

In the 1930s, fundamentalism was viewed by many as a "last gasp" vestige of something from the past[29] merely more recently, scholars accept shifted away from that view.[xxx] [31]

Changing interpretations [edit]

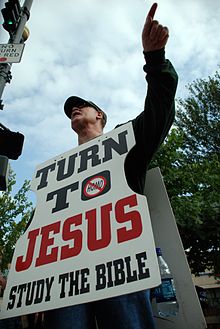

A Christian demonstrator preaching at Bele Chere

The interpretations given the fundamentalist motility take changed over time, with almost older interpretations being based on the concepts of social displacement or cultural lag.[xxx] Some in the 1930s, including H. Richard Niebuhr, understood the conflict between fundamentalism and modernism to be part of a broader social conflict between the cities and the land.[30] In this view the fundamentalists were state and pocket-size-town dwellers who were reacting against the progressivism of urban center dwellers.[thirty] Fundamentalism was seen as a form of anti-intellectualism during the 1950s; in the early on 1960s American intellectual and historian Richard Hofstadter interpreted it in terms of status anxiety.[xxx]

Beginning in the tardily 1960s, the movement began to be seen as "a bona fide religious, theological and even intellectual movement in its own correct."[30] Instead of interpreting fundamentalism as a simple anti-intellectualism, Paul Carter argued that "fundamentalists were simply intellectual in a way unlike than their opponents."[30] Moving into the 1970s, Earnest R. Sandeen saw fundamentalism as arising from the confluence of Princeton theology and millennialism.[30]

George Marsden defined fundamentalism as "militantly anti-modernist Protestant evangelicalism" in his 1980 piece of work Fundamentalism and American Culture.[xxx] "Militant" in this sense does not hateful "violent", information technology means "aggressively active in a cause".[32] Marsden saw fundamentalism arising from a number of preexisting evangelical movements that responded to various perceived threats by joining forces.[30] He argued that Christian fundamentalists were American evangelical Christians who in the 20th century opposed "both modernism in theology and the cultural changes that modernism endorsed. Militant opposition to modernism was what most clearly set off fundamentalism."[33] Others viewing militancy as a core characteristic of the fundamentalist motion include Philip Melling, Ung Kyu Pak and Ronald Witherup.[34] [35] [36] Donald McKim and David Wright (1992) argue that "in the 1920s, militant conservatives (fundamentalists) united to mount a conservative counter-offensive. Fundamentalists sought to rescue their denominations from the growth of modernism at abode."[37]

According to Marsden, contempo scholars differentiate "fundamentalists" from "evangelicals" by arguing the former were more militant and less willing to collaborate with groups considered "modernist" in theology. In the 1940s the more moderate faction of fundamentalists maintained the same theology but began calling themselves "evangelicals" to stress their less militant position.[38] Roger Olson (2007) identifies a more moderate faction of fundamentalists, which he calls "postfundamentalist", and says "most postfundamentalist evangelicals do not wish to be called fundamentalists, even though their bones theological orientation is not very unlike." Co-ordinate to Olson, a key event was the formation of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) in 1942.[39] Barry Hankins (2008) has a like view, saying "beginning in the 1940s....militant and separatist evangelicals came to be called fundamentalists, while culturally engaged and non-militant evangelicals were supposed to exist called evangelicals."[40]

Timothy Weber views fundamentalism as "a rather distinctive mod reaction to religious, social and intellectual changes of the tardily 1800s and early 1900s, a reaction that eventually took on a life of its own and changed significantly over fourth dimension."[30]

By region [edit]

In North America [edit]

Fundamentalist movements existed in nearly Northward American Protestant denominations by 1919 post-obit attacks on modernist theology in Presbyterian and Baptist denominations. Fundamentalism was especially controversial among Presbyterians.[41]

In Canada [edit]

In Canada, fundamentalism was less prominent,[42] merely an early leader was English-built-in Thomas Todhunter Shields (1873–1955), who led 80 churches out of the Baptist federation in Ontario in 1927 and formed the Wedlock of Regular Baptist Churches of Ontario and Quebec. He was affiliated with the Baptist Bible Union, based in the United States. His newspaper, The Gospel Witness, reached 30,000 subscribers in 16 countries, giving him an international reputation. He was one of the founders of the international Council of Christian Churches.[43]

Oswald J. Smith (1889–1986), reared in rural Ontario and educated at Moody Church building in Chicago, set up upwards The Peoples Church in Toronto in 1928. A dynamic preacher and leader in Canadian fundamentalism, Smith wrote 35 books and engaged in missionary work worldwide. Billy Graham called him "the greatest combination pastor, hymn author, missionary statesman, an evangelist of our time".[44]

In the The states [edit]

A leading organizer of the fundamentalist campaign against modernism in the U.s.a. was William Bell Riley, a Northern Baptist based in Minneapolis, where his Northwestern Bible and Missionary Preparation School (1902), Northwestern Evangelical Seminary (1935), and Northwestern Higher (1944) produced thousands of graduates. At a large conference in Philadelphia in 1919, Riley founded the Earth Christian Fundamentals Association (WCFA), which became the chief interdenominational fundamentalist system in the 1920s. Some marker this conference as the public start of Christian fundamentalism.[45] [46] Although the fundamentalist drive to take command of the major Protestant denominations failed at the national level during the 1920s, the network of churches and missions fostered by Riley showed that the movement was growing in forcefulness, especially in the U.S. South. Both rural and urban in character, the flourishing motion acted as a denominational surrogate and fostered a militant evangelical Christian orthodoxy. Riley was president of WCFA until 1929, later on which the WCFA faded in importance.[47] The Independent Fundamental Churches of America became a leading association of independent U.South. fundamentalist churches upon its founding in 1930. The American Quango of Christian Churches was founded for key Christian denominations every bit an alternative to the National Council of Churches.

J. Gresham Machen Memorial Hall

Much of the enthusiasm for mobilizing fundamentalism came from Protestant seminaries and Protestant "Bible colleges" in the The states. Two leading fundamentalist seminaries were the Dispensationalist Dallas Theological Seminary, founded in 1924 by Lewis Sperry Chafer, and the Reformed Westminster Theological Seminary, formed in 1929 under the leadership and funding of former Princeton Theological Seminary professor J. Gresham Machen.[48] Many Bible colleges were modeled afterward the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. Dwight Moody was influential in preaching the imminence of the Kingdom of God that was then of import to dispensationalism.[49] Bible colleges prepared ministers who lacked higher or seminary experience with intense study of the Bible, often using the Scofield Reference Bible of 1909, a Male monarch James Version of the Bible with detailed notes which interprets passages from a Dispensational perspective.

Although U.S. fundamentalism began in the North, the movement's largest base of pop support was in the Southward, peculiarly amongst Southern Baptists, where individuals (and sometimes entire churches) left the convention and joined other Baptist denominations and movements which they believed were "more than bourgeois" such as the Independent Baptist motility. By the belatedly 1920s the national media had identified information technology with the South, largely ignoring manifestations elsewhere.[50] In the mid-twentieth century, several Methodists left the mainline Methodist Church building and established fundamental Methodist denominations, such as the Evangelical Methodist Church and the Key Methodist Briefing (cf. conservative holiness motility); others preferred congregating in Contained Methodist churches, many of which are affiliated with the Association of Independent Methodists, which is fundamentalist in its theological orientation.[51] By the 1970s Protestant fundamentalism was securely entrenched and concentrated in the U.Due south. South. In 1972–1980 General Social Surveys, 65 percent of respondents from the "Due east S Fundamental" region (comprising Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Alabama) cocky-identified every bit fundamentalist. The share of fundamentalists was at or about 50 percent in "West S Central" (Texas to Arkansas) and "South Atlantic" (Florida to Maryland), and at 25 percent or beneath elsewhere in the country, with the low of nine percent in New England. The pattern persisted into the 21st century; in 2006–2010 surveys, the boilerplate share of fundamentalists in the East South Central Region stood at 58 percent, while, in New England, it climbed slightly to 13 percent.[52]

Evolution [edit]

In the 1920s, Christian fundamentalists "differed on how to understand the business relationship of cosmos in Genesis" but they "agreed that God was the writer of creation and that humans were distinct creatures, carve up from animals, and made in the image of God".[53] While some of them advocated the conventionalities in Old Globe creationism and a few of them fifty-fifty advocated the belief in evolutionary creation, other "strident fundamentalists" advocated Young Earth Creationism and "associated evolution with last-days disbelief".[53] These "strident fundamentalists" in the 1920s devoted themselves to fighting against the education of evolution in the nation's schools and colleges, especially by passing state laws that affected public schools. William Bong Riley took the initiative in the 1925 Scopes Trial by bringing in famed politico William Jennings Bryan and hiring him to serve as an assistant to the local prosecutor, who helped describe national media attending to the trial. In the half century later the Scopes Trial, fundamentalists had fiddling success in shaping government policy, and they were generally defeated in their efforts to reshape the mainline denominations, which refused to join fundamentalist attacks on evolution.[25] Particularly later on the Scopes Trial, liberals saw a partition betwixt Christians in favor of the instruction of evolution, whom they viewed as educated and tolerant, and Christians against evolution, whom they viewed as narrow-minded, tribal, obscurantist.[54]

Edwards (2000), nevertheless, challenges the consensus view among scholars that in the wake of the Scopes trial, fundamentalism retreated into the political and cultural groundwork, a viewpoint which is evidenced in the movie "Inherit the Wind" and the majority of contemporary historical accounts. Rather, he argues, the crusade of fundamentalism'south retreat was the death of its leader, Bryan. Most fundamentalists saw the trial as a victory rather than a defeat, but Bryan's death soon later on created a leadership void that no other fundamentalist leader could fill. Unlike the other fundamentalist leaders, Bryan brought proper name recognition, respectability, and the ability to forge a wide-based coalition of fundamentalist religious groups to contend in favor of the anti-evolutionist position.[55]

Gatewood (1969) analyzes the transition from the anti-evolution cause of the 1920s to the creation scientific discipline movement of the 1960s. Despite some similarities between these 2 causes, the creation science movement represented a shift from religious to pseudoscientific objections to Darwin'south theory. Creation science also differed in terms of pop leadership, rhetorical tone, and sectional focus. It lacked a prestigious leader similar Bryan, utilized pseudoscientific statement rather than religious rhetoric, and was a product of California and Michigan rather than the South.[56]

Webb (1991) traces the political and legal struggles between strict creationists and Darwinists to influence the extent to which evolution would be taught as scientific discipline in Arizona and California schools. After Scopes was convicted, creationists throughout the U.s.a. sought similar antievolution laws for their states. These included Reverends R. S. Aggravate and Aubrey 50. Moore in Arizona and members of the Creation Research Society in California, all supported by distinguished laymen. They sought to ban development every bit a topic for report, or at least relegate it to the status of unproven theory perhaps taught alongside the biblical version of creation. Educators, scientists, and other distinguished laymen favored evolution. This struggle occurred later in the Southwest than in other US areas and persisted through the Sputnik era.[57]

In contempo times, the courts have heard cases on whether or not the Volume of Genesis's creation account should be taught in science classrooms alongside evolution, about notably in the 2005 federal courtroom case Kitzmiller v. Dover Surface area School District.[58] Creationism was presented under the banner of intelligent design, with the book Of Pandas and People being its textbook. The trial ended with the gauge deciding that instruction intelligent design in a scientific discipline class was unconstitutional as it was a religious belief and non science.[59]

The original fundamentalist movement divided forth clearly defined lines within conservative evangelical Protestantism as issues progressed. Many groupings, large and small, were produced past this schism. Neo-evangelicalism, the Heritage move, and Paleo-Orthodoxy have all adult distinct identities, simply none of them acknowledge any more than an historical overlap with the fundamentalist motility, and the term is seldom used of them. The holonym "evangelical" includes fundamentalists also as people with similar or identical religious beliefs who do non appoint the outside claiming to the Bible as actively.[threescore]

Christian right [edit]

The latter half of the twentieth century witnessed a surge of involvement in organized political activism by U.S. fundamentalists. Dispensational fundamentalists viewed the 1948 establishment of the state of State of israel as an of import sign of the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, and back up for Israel became the centerpiece of their approach to U.Southward. strange policy.[61] U.s.a. Supreme Court decisions also ignited fundamentalists' involvement in organized politics, particularly Engel 5. Vitale in 1962, which prohibited state-sanctioned prayer in public schools, and Abington School District v. Schempp in 1963, which prohibited mandatory Bible reading in public schools.[62] By the time Ronald Reagan ran for the presidency in 1980, fundamentalist preachers, like the prohibitionist ministers of the early 20th century, were organizing their congregations to vote for supportive candidates.[63]

Leaders of the newly political fundamentalism included Rob Grant and Jerry Falwell. Beginning with Grant's American Christian Cause in 1974, Christian Voice throughout the 1970s and Falwell's Moral Majority in the 1980s, the Christian Right began to have a major bear upon on American politics. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Christian Right was influencing elections and policy with groups such every bit the Family Research Council (founded 1981 by James Dobson) and the Christian Coalition (formed in 1989 by Pat Robertson) helping conservative politicians, especially Republicans, to win state and national elections.[64]

In Australia [edit]

There are, in Australia, a few examples of the more than extreme, American-style fundamentalist cult-like forms of Pentecostalism. The counter marginal trend, represented most notably past the Logos Foundation led past Howard Carter in Toowoomba, Queensland, and later by "manifest celebrity" movements tin be institute in congregations such as the Range Christian Fellowship.

The Logos Foundation, an influential and controversial Christian ministry, flourished in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s under the leadership of Howard Carter, originally a Baptist pastor from Auckland in New Zealand. Logos Foundation was initially a trans-denominational charismatic educational activity ministry; its members were primarily Protestant simply it besides had some ties with Roman Catholic lay-groups and individuals.[65]

Logos Foundation was Reconstructionist, Restorationist, and Dominionist in its theology and works. Paul Collins established the Logos Foundation c. 1966 in New Zealand equally a trans-denominational education ministry building which served the Charismatic Renewal by publishing the Logos Magazine. c. 1969 Paul Collins moved it to Sydney in Australia, where it also facilitated large trans-denominational renewal conferences in venues such as Sydney Town Hall and the Wentworth Hotel. It was transferred[ by whom? ] to Howard Carter's leadership, relocating to Hazelbrook in the lower Blue Mountains of New S Wales, where it operated for a few years, and in the mid-1970s, information technology was transferred to Blackheath in the upper Blue Mountains. During these years the education ministry attracted agreeing fellowships and home groups into a loose association with it.

Publishing became a significant operation, distributing charismatic-themed and Restorationist teachings focused on Christian maturity and Christ's pre-eminence in short books and the monthly Logos/Restore Magazine (associated with New Wine Magazine in the United States). It held almanac calendar week-long conferences of over 1,000 registrants, featuring international charismatic speakers, including Derek Prince, Ern Baxter, Don Basham, Charles Simpson, Bob Mumford, Kevin Conner (Australia), Peter Morrow (New Zealand) and others.

A Bible college was also established[ past whom? ] nearby at Westwood Society, Mount Victoria. At the principal site in Blackheath a Christian 1000-12 school, Mountains Christian University was established which became a forerunner of more widespread Christian independent schools and dwelling house-schooling as a hallmark of the motion. It carried over the Old Covenant practice of tithing (to the local church), and expected regular sacrificial giving beyond this.

Theologically the Logos Foundation taught orthodox Christian core beliefs – however, in matters of opinion Logos teaching was presented[ by whom? ] as authoritative and alternative views were discouraged. Those who questioned this teaching eventually tended to leave the motion. Over fourth dimension, a strong cult-like culture of grouping conformity developed and those who dared to question it were apace brought into line by other members who gave automatic responses which were shrouded in spiritualised expressions. In some instances the leadership enforced unquestioning compliance by engaging in bullying-type behavior. The grouping viewed itself as being separate from "the world" and it fifty-fifty regarded alternative views and other expressions, denominations or interpretations of Christianity with distrust at worst only considered nearly of them fake at all-time.

From the mid-1970s a hierarchical ecclesiology was adopted in the form of the Shepherding Motility's whole-of-life discipleship of members by personal pastors (normally their "cell group" leaders), who in turn were also answerable to their personal pastors. Followers were informed that even their leader, Howard Carter, related as a disciple to the churchly grouping in Christian Growth Ministries of Bob Mumford, Charles Simpson, Ern Baxter, Derek Prince, and Don Basham, in Ft Lauderdale, Us (whose network was estimated[ by whom? ] to accept approx. 150,000 people involved at its peak c. 1985). Howard Carter's primary pastoral relationship was with Ern Baxter, a pioneer of the Healing Revival of the 1950s and of the Charismatic Renewal of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Written covenants of submission to the individual church pastors were encouraged for the members of ane representative church building, Christian Religion Centre (Sydney), and were said[ by whom? ] to be mutual practice throughout the movement at the time.

In 1980 the Logos motility churches adopted the proper name "Australian Fellowship of Covenant Communities" (AFoCC), and were led through an eschatological shift in the early on 1980s from the pre-millennialism of many Pentecostals (described as a theology of defeat), to the post-millennialism of the Presbyterian Reconstructionist theonomists (described as a theology of victory). A shift to an overt theological-political prototype resulted in some senior leadership, including Pastor David Jackson of Christian Faith Centre Sydney, leaving the motility altogether. In the mid-1980s AFoCC re-branded nonetheless over again as the "Covenant Evangelical Church" (not associated with the Evangelical Covenant Church in the US). The Logos Foundation brand-name connected as the educational, commercial and political arm of the Covenant Evangelical Church building.

The group moved for the final time in 1986 to Toowoomba in Queensland where in that location were already associated fellowships and a demographic environment highly conducive to the growth of extreme right-fly religio-political movements. This fertile footing saw the movement peak in a short time, reaching a local support base of upwardly of 2000 people.[66]

The move to Toowoomba involved much training, including members selling homes and other avails in New South Wales and the Logos Foundation acquiring many homes, businesses and commercial backdrop in Toowoomba and the Darling Downs.

In the process of relocating the arrangement and about of its members, he Covenant Evangelical Church absorbed a number of other minor Christian churches in Toowoomba. Some of these were house churches/groups more or less affiliated with Carter'southward other organisations. Carter and some of his followers attempted to make links with Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen (in role 1968–1987), a known Christian conservative, in order to farther their goals.

Carter continued to atomic number 82 the shift in eschatology to post-millennialism and prominently religio-political in nature. More of his leadership team left the movement every bit Carter'southward style became more authoritarian and cultish. Colin Shaw, who was a key member at this time, believed that Pastor Howard Carter was an "anointed homo of God", and Shaw later became the "right-hand" man of Carter in his "outreach and missionary works" in Quezon City in the Philippines. Logos used a Filipino church, the Christian Renewal Center (a moderate Pentecostal/Charismatic church building) as their base to accelerate and promote the teachings of the Shepherding Movement. With local assistance in the Philippines, Colin Shaw coordinated and sponsored (under the Christian Renewal Eye's name) conferences featuring Carter. Many poorly-educated and sincere Filipino pastors and locals, commonly from small-scale churches, were convinced to support the wider Logos movement with tithes that were collected from their limited funds. However, soon after the revelations of Howard Carter's scandalous immorality and corrupt lifestyle broke, the Filipino wing of Logos dissolved and its former members dispersed back into established local churches. Colin Shaw was said[ by whom? ] to have abandoned the Shepherding Motility at this time and for a time after that, he engaged in soul-searching and cocky-exile, fueled by astringent guilt over the way the Filipino Christians were manipulated.

In 1989 Logos controversially involved itself in the Queensland state election, running a campaign of surveys and full-page newspaper advertisements promoting the line that candidates' adherence to Christian principles and biblical ideals was more important than the widespread abuse in the Queensland government that had been revealed by the Fitzgerald Inquiry. Published advertisements in the Brisbane paper The Courier-Mail service at the time promoted strongly conservative positions in opposition to pornography, homosexuality and abortion, and a return to the expiry penalty. Some supporters controversially advocated Old Testament laws and penalties.[67] This activeness backfired sensationally, with many mainstream churches, community leaders and religious organisations distancing themselves from the Logos Foundation after making public statements denouncing it.[65] At times the capital punishment for homosexuals was advocated, in accordance with Quondam Attestation Constabulary.[68] [69] The Sydney Forenoon Herald subsequently described part of this campaign when the Logos Foundation campaigned: "Homosexuality and censorship should determine your vote, the electorate was told; abuse was not the major business concern."[seventy] The same article quoted Carter from a letter he had written to supporters at the time, "The greenies, the gays and the greedy are marching. At present the Christians, the conservatives and the concerned must march also." These views were not new. An before article published in the Herald quoted a Logos spokesman in reference to the call for the death penalty for homosexuals in order to rid Queensland of such people, who stated "the fact a law is on the statutes is the all-time safeguard for society".[71]

Although similar behaviours had existed previously, these last years in Queensland saw Logos Foundation increasingly developing cult-like tendencies.[ citation needed ] This authoritarian environs degenerated into a perverse and unbiblical abuse of power.[ commendation needed ] Obedience and unhealthy submission to human leaders was cultish in many ways and the concept of submission for the purpose of "spiritual covering" became a dominant theme in Logos Foundation teaching. The idea of spiritual roofing shortly degenerated into a organization of overt abuse of ability and excessive control of people's lives.[ citation needed ] This occurred despite growing opposition to the Shepherding motion from respected Evangelical and Pentecostal leaders in the United States, showtime as early as 1975. Nonetheless, in Commonwealth of australia, through the Logos Foundation and Covenant Evangelical Church, this move flourished across the time when information technology had effectively entered a period of pass up in Northward America. Carter effectively quarantined followers in Australia from the truth of what had begun to play out in the U.Southward.A.[ citation needed ]

The motion had ties to a number of other groups including World MAP (Ralph Mahoney), California; Christian Growth Ministries, Fort Lauderdale; and Rousas Rushdoony, the male parent of Christian Reconstructionism in the United states of america. Activities included printing, publishing, conferencing, home-schooling and ministry-training. Logos Foundation (Australia) and these other organizations at times issued theological qualifications and other plainly academic degrees, master's degrees and doctorates following no formal procedure of written report or recognized rigour, ofttimes under a range of dubious names that included the give-and-take "University". In 1987 Carter conferred on himself a Primary of Arts degree which was patently issued by the Pacific College Theological,[ citation needed ] an institution whose existence investigating journalists take failed to verify. Carter frequently gifted such "qualifications" to visiting preachers from the Us - including a PhD purportedly issued by the University of Oceania Sancto Spiritus'. The recipient thereafter used the title of Doctor in his itinerant preaching and revival ministry throughout North America.[ commendation needed ]

The Shepherding Motion worldwide descended into a cultish motion characterized by manipulative relationships, abuse of power and dubious financial arrangements.[ citation needed ] It had been an try by mostly[ quantify ] sincere people to free Christianity of the entrenched reductions of traditional and consumerist religion. Nevertheless, with its emphasis on authority and submissive accountability, the movement was open to abuse. This, combined with spiritual hunger, an early measure of success and growth, mixed motives, and the inexperience of new leaders all coalesced to form a dangerous and volatile mix. Howard Carter played these factors skillfully to entrench his own position.

The Logos Foundation and Covenant Evangelical Church did not long survive the scandal of Howard Carter's standing down and public exposure of adultery in 1990. Hey (2010) has stated in his thesis: "Suggested reasons for Carter'southward failure accept included insecurity, an disability to open up upwards to others, airs and over conviction in his own power".[66] As with many modern evangelists and mega-church leaders, followers within the movement placed him on a pedestal. This surround where the leader was not subject to true accountability allowed his charade and double life to flourish unknown for many years. In the years immediately prior to this scandal, those who dared to question were quickly derided by other members or fifty-fifty disciplined, thus reinforcing a very unhealthy environment. When the scandal of Carter'southward immorality was revealed, total details of the lavish lifestyle to which he had get accustomed were also exposed. Carter's frequent travel to Due north America was lavish and extravagant, utilizing first-class flights and five-star hotels. The full fiscal diplomacy of the organisation prior to the plummet were highly secretive. Almost members had been unaware of how vast sums of coin involved in the whole operation were channelled, nor were they aware of how the leaders' admission to these funds was managed.

A significant number of quite senior ex-Logos members found credence in the now-defunct Rangeville Uniting Church building. The congregation of the Rangeville Uniting Church left the Uniting Church to become an independent congregation known as the Rangeville Community Church building. Prior to the Rangeville Uniting Church closing, an earlier carve up resulted in a significant percentage of the total congregation contributing to the formation of the Range Christian Fellowship in Blake Street in Toowoomba.

The Range Christian Fellowship in Blake Street, Toowoomba, has a reputation for exuberant worship services and the public manifestation of charismatic phenomena and manifestations[ citation needed ] that place information technology well exterior of mainstream Pentecostal church expression. It is perhaps[ original research? ] one of the prime Australian examples of churches which are associated with the New Apostolic Reformation, a fundamentalist Pentecostal religious right wing movement which American journalist Forrest Wilder has described as follows: "Their beliefs can tend toward the bizarre. Some prophets fifty-fifty merits to have seen demons at public meetings. They've taken biblical literalism to an extreme".[72] Information technology operates in a converted squash-centre[73] and was established on 9 Nov 1997[74] as a group which bankrupt away from the Rangeville Uniting Church in Toowoomba over disagreements with the national leadership of the Uniting Church building in Australia. These disagreements predominantly related to the ordination of homosexual people into ministry building.[75] The Range Christian Fellowship's diverse origins resulted in a divergent mix of worship preferences, expectations and issues. The church building initially met in a Seventh-day Adventist Church hall before purchasing the property in Blake Street, leaving the congregation heavily indebted,[76] often close to bankruptcy,[77] and with a high turnover of congregants.[78] The congregation attributes their continued avoidance of fiscal collapse to God'due south blessing and regards this as a miracle.[79]

Whilst adhering to Protestant behavior, the church supplements these beliefs with influences from the New Apostolic Reformation, revivalism, Dominion theology, Kingdom At present theology, Spiritual Warfare Christianity and Five-fold ministry thinking. Scripture is interpreted literally, though selectively. Unusual manifestations attributed to the Holy Spirit or the presence of "the anointing" include women (and at times even men) moaning and retching equally though experiencing child birth,[80] with some claiming to be having actual contractions of the womb (known as "spiritual birthing").[81] Dramatic and apocalyptic predictions regarding the future were particularly axiomatic during the time leading up to Y2K, when a number of prophecies were publicly shared, all of which were proven faux past subsequent events. Attendees are given a high degree of freedom, influenced in the church building'due south initial years past the promotion of Jim Rutz's publication, "The Open Church building", resulting in broad tolerance of expressions of revelation, a "give-and-take from the Lord" or prophecy.

At times, people within the fellowship claim to have seen visions - in dreams, whilst in a trance-like state during worship, or during moments of religious ecstasy - with these experiences frequently conveying a revelation or prophecy. Other occurrences accept included people challenge to take been in an altered land of consciousness (referred to as "resting in the Lord" and "slain in the spirit" - amidst other names), characterized by reduced external awareness and expanded interior mental and spiritual awareness, often accompanied past visions and emotional (and sometimes physical) euphoria. The church has hosted visits from various Christian leaders who claim to be modern-day Apostles as well equally from many others who claim to exist prophets or faith healers. Perhaps surprisingly, speaking in tongues, which is mutual in other Pentecostal churches, also occurs but it is not frequent nor is it promoted; and it is rarely witnessed in public gatherings. Neo-charismatic elements are rejected elsewhere in classical Pentecostalism, such as the Prayer of Jabez, prosperity theology, the Toronto Blessing (with its emphasis on strange, non-verbal expressions), George Otis' Spiritual Warfare, the Brownsville Revival (Pensacola Outpouring), Morningstar Ministries, the Lakeland Revival, and the Vineyard group of churches, have been influential. The church has always been known for its vibrant and occasionally euphoric and ecstatic worship services, services featuring music, vocal, dancing, flags and banners. Range Christian Fellowship is office of the church unity movement in Toowoomba, with other like-minded churches (mainstream traditional denominations take a separate ecumenical grouping).[82] [83] [84] This group, known as the Christian Leaders' Network, aspires to be a Christian right-wing influence grouping inside the urban center, at the centre of a hoped-for corking revival during which they volition "take the city for the Lord". The Range Christian Fellowship has wholeheartedly thrown itself into citywide events that are viewed[ by whom? ] every bit a foundation for stimulating revival, which have included Easterfest, "Christmas the Full Story",[85] and continuous 24-hour worship-events.[86]

The church retains an impressive resilience which information technology has inherited from its Uniting Church, which has seen information technology conditions difficult times. Its beliefs and actions, which place information technology on the fringes of both mainstream and Pentecostal Christianity, are largely confined to its Lord's day gatherings and gatherings which are privately held in the homes of its members. Criticism of the church is regarded every bit a bluecoat of honor by some of its members, because they view it in terms of the expected persecution of the holy remnant of the true church building in the final days. The church continues to exist fatigued to, and to acquaintance itself with fringe Pentecostal and fundamentalist movements, particularly those which originated in North America, most recently with Doug Addison's.[87] Addison has become known for delivering prophecies through dreams and unconventionally through people's torso tattoos, and he mixes highly fundamentalist Christianity with elements of psychic spirituality.[88]

By denomination [edit]

Contained Baptist [edit]

Conservative Holiness Movement [edit]

Fundamental Methodism includes several connexions, such equally the Evangelical Methodist Church and Fundamental Methodist Conference.[89] Additionally, Methodist connexions in the bourgeois holiness motion herald the beliefs of "separation from the world, from false doctrines, from other ecclesiastical connections" as well as place heavy emphasis on practicing holiness standards.[90]

Nondenominationalism [edit]

In nondenominational Christianity of the evangelical diversity, the word "biblical" or "independent" often appears in the proper noun of the church or denomination.[28] The independence of the church is claimed and affiliation with a Christian denomination is infrequent, although at that place are fundamentalist denominations.[91]

Reformed fundamentalism [edit]

Reformed fundamentalism includes those denominations in the Reformed tradition (which includes the Continental Reformed, Presbyterian, Reformed Anglican and Reformed Baptist Churches) who adhere to the doctrine of biblical infallibility and lay heavy emphasis on historic confessions of faith, such equally the Westminster Confession.[92] [7]

Examples of Reformed fundamentalist denominations include the Orthodox Presbyterian Church[92] and the Gratis Presbyterian Church of Ulster.

Criticism [edit]

Fundamentalists' literal interpretation of the Bible has been criticized past practitioners of biblical criticism for failing to take into account the circumstances in which the Christian Bible was written. Critics claim that this "literal estimation" is non in keeping with the message which the scripture intended to convey when it was written,[93] and it also uses the Bible for political purposes past presenting God "more as a God of sentence and penalization than every bit a God of love and mercy".[94]

Christian fundamentalism has also been linked to child abuse[95] [96] [97] and mental affliction[98] [99] [100] as well as to corporal punishment,[101] [102] [103] with most practitioners assertive that the Bible requires them to spank their children.[104] [105] Artists take addressed the issues of Christian fundamentalism,[106] [107] with one providing a slogan "America's Premier Child Abuse Brand".[108]

Fundamentalists accept attempted and go along to effort to teach intelligent design, a hypothesis with creationism as its base of operations, in lieu of development in public schools. This has resulted in legal challenges such as the federal instance of Kitzmiller v. Dover Expanse School Commune which resulted in the United States District Court for the Center District of Pennsylvania ruling the pedagogy of intelligent design to be unconstitutional due to its religious roots.[109]

See too [edit]

- Bible Belt

- Christian fascism

- Christian nationalism

- Christian reconstructionism

- Christian right

- Christian values

- Christian Zionism

- Conservative evangelicalism in the United Kingdom

- A. C. Dixon

- Glossary of Christianity

- Hindu fundamentalism

- H. A. Ironside

- Islamic fundamentalism

- Jewish fundamentalism

- Dwight 50. Moody

- Moderate Christianity

- Mormon fundamentalism

- Plymouth Brethren

- Reformed fundamentalism

- Religious abuse

- Religious intolerance

- Baton Sunday

- R. A. Torrey

- Traditionalist Catholicism

- True Orthodox church

- Zionism

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Fundamentalism". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ a b Marsden (1980), pp. 55–62, 118–23.

- ^ Sandeen (1970), p. vi

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1988). The Encyclopedia of American Religions, Religious Creeds: A Compilation of More Than 450 Creeds, Confessions, Statements of Religion, and Summaries of Doctrine of Religious and Spiritual Groups in the United States and Canada. Gale Research Company. p. 565. ISBN978-0-8103-2132-8.

Statements of faith from fundamentalist churches will ofttimes affirm both infallibility and inerrancy.

- ^ "Britannica Academic". academic.eb.com . Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Zamora, Lois Parkinson (1982). The Apocalyptic Vision in America: Interdisciplinary Essays on Myth and Civilization. Bowling Green University Popular Press. p. 55. ISBN978-0-87972-190-9.

Hence it is impossible to speak of fundamentalists as a detached grouping. Rather, one must speak of fundamentalist Baptists, fundamentalist Methodists, fundamentalist Presbyterians, fundamentalist independents, and the like.

- ^ a b Carter, Paul (18 March 2019). "What Is a Reformed Fundamentalist?". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Gasper, Louis (18 May 2020). The Fundamentalist Movement. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 39. ISBN978-iii-11-231758-7.

- ^ Jones, Julie Scott (15 April 2016). Existence the Chosen: Exploring a Christian Fundamentalist Worldview. Routledge. ISBN978-ane-317-17535-3.

- ^ Colina, Brennan; Knitter, Paul F.; Madges, William (1997). Faith, Religion & Theology: A Contemporary Introduction. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 326. ISBN978-0-89622-725-5.

Cosmic fundamentalists, similar their Protestant counterparts, fright that the church has abandoned the unchanging truth of past tradition for the evolving speculations of modernistic theology. They fright that Christian societies have replaced systems of absolute moral norms with subjective decision making and relativism. Similar Protestant fundamentalists, Catholic fundamentalists advise a worldview that is rigorous and clear cut.

- ^ Waldman, Steve; Light-green, John C. (29 April 2004). "Evangelicals v. Fundamentalists". pbs.org/wgbh. Frontline: The Jesus Gene. Boston: PBS/WGBH. Retrieved 9 Oct 2021.

- ^ Robbins, Dale A. (1995). What is a Fundamentalist Christian?. Grass Valley, California: Victorious Publications. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved i December 2009.

- ^ Horton, Ron. "Christian Education at Bob Jones University". Greenville, South Carolina: Bob Jones University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 1 Dec 2009.

- ^ Wilson, William P. "Legalism and the Authorization of Scripture". Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ Morton, Timothy S. "From Liberty to Legalism – A Candid Study of Legalism, "Pharisees," and Christian Freedom". Retrieved xix March 2010.

- ^ Sandeen (1970), ch 1

- ^ a b Woodberry, Robert D; Smith, Christian S. (1998). "Fundamentalism et al: conservative Protestants in America". Annual Review of Folklore. 24 (1): 25–56. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.25 – via AcademicOne File.

- ^ Hans J. Hillerbrand, Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set, Routledge, UK, 2004, p. 390

- ^ Randall Herbert Balmer, Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism: Revised and expanded edition, Baylor Academy Printing, U.s., 2004, p. 278

- ^ "The Fundamentals A Testimony to the Truth". Archived from the original on 1 January 2003. Retrieved 25 Oct 2009.

- ^ George One thousand. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, Oxford Academy Press, Britain, 1980, p. 20

- ^ Luc Chartrand, La Bible au pied de la lettre, Le fondamentalisme questionné, Mediaspaul, France, 1995, p. 20

- ^ Marsden (1980), pp 109–118

- ^ Sandeen (1970) pp 103–31

- ^ a b Kee, Howard Clark; Emily Albu; Carter Lindberg; J. William Frost; Dana Fifty. Robert (1998). Christianity: A Social and Cultural History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 484. ISBN0-13-578071-3.

- ^ Marsden, George M. (1995). Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 118. ISBN978-0-8028-0870-7.

- ^ Beyond Biblical Literalism and Inerrancy: Conservative Protestants and the Hermeneutic Interpretation of Scripture, John Bartkowski, Sociology of Religion, 57, 1996.

- ^ a b Samuel Southward. Hill, The New Encyclopedia of Southern Civilisation: Volume 1: Organized religion, University of Due north Carolina Press, USA, 2006, p. 77

- ^ Parent, Mark (1998). Spirit Scapes: Mapping the Spiritual & Scientific Terrain at the Dawn of the New Millennium. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. p. 161. ISBN978-1-77064-295-9.

By the beginning of the 1930s [...] fundamentalism appeared to be in disarray everywhere. Scholarly studies sprang up which claimed that fundamentalism was the last gasp of a dying religious lodge that was speedily vanishing.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Reid, D. K., Linder, R. D., Shelley, B. 50., & Stout, H. S. (1990). In Lexicon of Christianity in America. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Printing. Entry on Fundamentalism

- ^ Hankins, Barry (2008). "'We're All Evangelicals Now': The Existential and Backward Historiography of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism". In Harper, Keith (ed.). American Denominational History: Perspectives on the Past, Prospects for the Future. Religion & American Culture. Vol. 68. Academy of Alabama Printing. p. 196. ISBN978-0-8173-5512-8.

[...] in 1970 [...] Ernest Shandeen's The Roots of Fundamentalism [...] shifted the estimation abroad from the view that fundamentalism was a terminal-gasp attempt to preserve a dying way of life.

- ^ "Militant" in Merriam Webster Third Unabridged Lexicon (1961) which cites "militant suffragist" and "militant trade unionism" equally instance.

- ^ Marsden (1980), Fundamentalism and American Culture p. four

- ^ Philip H. Melling, Fundamentalism in America: millennialism, identity and militant organized religion (1999). Equally another scholar points out, "I of the major distinctives of fundamentalism is militancy."

- ^ Ung Kyu Pak, Millennialism in the Korean Protestant Church (2005) p. 211.

- ^ Ronald D. Witherup, a Cosmic scholar, says: "Essentially, fundamentalists come across themselves as defending authentic Christian religion... The militant aspect helps to explain the want of fundamentalists to get active in political change." Ronald D. Witherup, Biblical Fundamentalism: What Every Catholic Should Know (2001) p two

- ^ Donald Thou. McKim and David F. Wright, Encyclopedia of the Reformed faith (1992) p. 148

- ^ George M. Marsden (1995). Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. xi. ISBN978-0-8028-0870-7.

- ^ Roger E. Olson, Pocket History of Evangelical Theology (2007) p. 12

- ^ Barry Hankins, Francis Schaeffer and the shaping of Evangelical America (2008) p 233

- ^ Marsden, George Grand. (1995). Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 109–118. ISBN978-0-8028-0870-seven.

- ^ John G. Stackhouse, Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century (1993)

- ^ C. Allyn Russell, "Thomas Todhunter Shields: Canadian Fundamentalist," Foundations, 1981, Vol. 24 Result i, pp 15–31

- ^ David R. Elliott, "Knowing No Borders: Canadian Contributions to American Fundamentalism," in George A. Rawlyk and Mark A. Noll, eds., Astonishing Grace: Evangelicalism in Australia, Uk, Canada, and the U.s.a. (1993)

- ^ Trollinger, William (8 Oct 2019). "Fundamentalism turns 100, a landmark for the Christian Correct". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Sutton, Matthew Avery (25 May 2019). "The Twenty-four hours Christian Fundamentalism Was Born". The New York Times . Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ William Vance Trollinger, Jr. "Riley's Empire: Northwestern Bible School and Fundamentalism in the Upper Midwest". Church building History 1988 57(two): 197–212. 0009–6407

- ^ Marsden, George M. (1995). Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 33. ISBN978-0-8028-0870-vii.

- ^ Kee, Howard Clark; Emily Albu; Carter Lindberg; J. William Frost; Dana L. Robert (1998). Christianity: A Social and Cultural History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 484.

- ^ Mary Beth Swetnam Mathews, Rethinking Zion: how the print media placed fundamentalism in the Due south (2006) page xi

- ^ Crespino, Joseph (2007). In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution. Princeton University Press. p. 169. ISBN978-0-691-12209-0.

- ^ "General Social Survey database".

- ^ a b Sutton, Matthew Avery (25 May 2019). "The Day Christian Fundamentalism Was Born". The New York Times . Retrieved 26 May 2019.

Although fundamentalists differed on how to empathize the account of creation in Genesis, they agreed that God was the author of creation and that humans were distinct creatures, separate from animals, and made in the image of God. Some believed than an old world could be reconciled with the Bible, and others were comfy teaching some forms of God-directed evolution. Riley and the more strident fundamentalists, withal, associated evolution with final-days atheism, and they made it their mission to purge it from the schoolroom.

- ^ David Goetz, "The Monkey Trial". Christian History 1997 16(iii): 10–xviii. 0891–9666; Burton Westward. Folsom, Jr. "The Scopes Trial Reconsidered." Continuity 1988 (12): 103–127. 0277–1446, by a leading conservative scholar

- ^ Mark Edwards, "Rethinking the Failure of Fundamentalist Political Antievolutionism after 1925". Fides Et Historia 2000 32(two): 89–106. 0884–5379

- ^ Willard B. Gatewood, Jr., ed. Controversy in the Twenties: Fundamentalism, Modernism, & Evolution (1969)

- ^ Webb, George E. (1991). "The Evolution Controversy in Arizona and California: From the 1920s to the 1980s". Journal of the Southwest. 33 (ii): 133–150. Come across as well Curtis, Christopher Chiliad. (1986). "Mississippi's Anti-Evolution Police force of 1926". Periodical of Mississippi History. 48 (ane): fifteen–29.

- ^ "Kitzmiller v. Dover: Intelligent Design on Trial". National Center for Science Pedagogy. 17 October 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ s:Kitzmiller five. Dover Expanse School District et al., H. Conclusion

- ^ Harris, Harriet A. Fundamentalism and Evangelicals (2008), pp. 39, 313.

- ^ Aaron William Rock, Dispensationalism and U.s. strange policy with State of israel (2008) extract

- ^ Bruce J. Dierenfield, The Battle over Schoolhouse Prayer (2007), page 236.

- ^ Oran Smith, The Rise of Baptist Republicanism (2000)

- ^ Albert J. Menendez, Evangelicals at the Ballot Box (1996), pp. 128–74.

- ^ a b Harrison, John. The Logos Foundation: The rise and fall of Christian Reconstructionism in Australia (PDF). Schoolhouse of Journalism & Communication, The University of Queensland.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Sydney Forenoon Herald, 13 Oct 1990, "Sexual activity Scandal – Bible Belt", p.74

- ^ p.3

- ^ "Sex activity Scandal – Bible Belt", Sydney Morning time Herald, xiii October 1990, p.74

- ^ Roberts, G., "Sexual practice Scandal Divides Bible Belt", Sydney Morning Herald, 12 Oct 1990.

- ^ Lyons, J., "God Remains an Issue in Queensland", Sydney Morning time Herald, 18 November 1989.

- ^ "Rick Perry's Army of God". 3 Baronial 2011.

- ^ Hart, Timothy. "Church Detect". Retrieved ten September 2016.

- ^ Small 2004, p. 293

- ^ Small 2004, p. 287

- ^ Small 2004, pp. 299–300

- ^ Small 2004, p. 358

- ^ Pocket-size 2004, p. 306

- ^ Pocket-size 2004, p. 316

- ^ "TRAVAIL AND APOSTOLIC ORDER – Vision International Ministries".

- ^ quaternary paragraph

- ^ "Christian Leaders' Network". Facebook. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "One Metropolis I Church One Heart". Toowoomba Christian Leaders' Network. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Christian Fellowship, The Range. "The Range Christian Fellowship". Facebook. Retrieved 17 Jan 2015.

- ^ Small 2004, p. 297

- ^ Pocket-size 2004, p. 308

- ^ "The Range Christian Fellowship". Facebook.

- ^ "When psychology meets psychic -".

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas; Lamport, Mark A. (10 Nov 2016). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 931. ISBN978-1-4422-4432-0.

- ^ Graham, Andrew James (2013). Conservative Holiness Pastsors' Ability to Assess Depression and their Willingness to refer to Mental Wellness Professionals. Freedom Academy. p. 16.

- ^ Samuel S. Hill, Charles H. Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson, Encyclopedia of Organized religion in the South, Mercer University Printing, USA, 2005, p. 336

- ^ a b Dorrien, Gary J. (one January 1998). The Remaking of Evangelical Theology. Westminster John Knox Printing. p. 42. ISBN978-0-664-25803-0.

- ^ "A Critique of Fundamentalism". infidels.org . Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Brennan Hill; Paul F. Knitter; William Madges (1997). Faith, Religion & Theology: A Contemporary Introduction. Xx-Tertiary Publications. ISBN978-0-89622-725-five.

In fundamentalists circles, both Catholic and Protestant, God is often presented more than as a God of judgment and punishment than as a God of beloved and mercy.

- ^ "Fundamentalist Christianity and Child Abuse: A Taboo Topic". Psychology Today . Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Brightbill, Kathryn. "The larger problem of sexual corruption in evangelical circles". chicagotribune.com . Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "The reported decease of the 'White Widow' and her 12-yr-erstwhile son should brand united states of america face some difficult facts". The Independent. 12 Oct 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Bennett-Smith, Meredith (31 May 2013). "Kathleen Taylor, Neuroscientist, Says Religious Fundamentalism Could Be Treated Equally A Mental Illness". Huffington Mail service . Retrieved 4 Oct 2017.

- ^ Morris, Nathaniel P. "How Exercise Y'all Distinguish betwixt Religious Fervor and Mental Illness?". Scientific American Weblog Network . Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Religious fundamentalism a mental disease? | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 6 Nov 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Grasmick, H. G.; Bursik, R. J.; Kimpel, Thou. (1991). "Protestant fundamentalism and attitudes toward corporal penalty of children". Violence and Victims. vi (iv): 283–298. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.half-dozen.4.283. ISSN 0886-6708. PMID 1822698. S2CID 34727867.

- ^ "Religious Attitudes on Corporal Penalization -". Retrieved iv October 2017.

- ^ "Christian fundamentalist schools 'performed claret curdling exorcisms on children'". The Independent. 16 September 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Newhall, Barbara Falconer (10 Oct 2014). "James Dobson: Beat Your Domestic dog, Spank Your Kid, Go to Heaven". Huffington Post . Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Spanking in the Spirit?". CT Women . Retrieved viii October 2017.

- ^ "Can Art Relieve Us From Fundamentalism?". Religion Dispatches. 2 March 2017. Retrieved iv October 2017.

- ^ Hesse, Josiah (5 April 2016). "Apocalyptic upbringing: how I recovered from my terrifying evangelical babyhood". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved iv October 2017.

- ^ "ESC by Daniel Vander Ley". world wide web.artprize.org . Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Victory in the Challenge to Intelligent Design". American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

Bibliography [edit]

- Almond, Gabriel A., R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan, eds. (2003). Strong Religion: The Ascension of Fundamentalisms around the World and text search

- Armstrong, Karen (2001). The Boxing for God. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-39169-ane.

- Ballmer, Randall (2nd ed 2004). Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism

- Ballmer, Randall (2010). The Making of Evangelicalism: From Revivalism to Politics and Beyond, 120pp

- Ballmer, Randall (2000). Blessed Assurance: A History of Evangelicalism in America

- Beale, David O. (1986). In Pursuit of Purity: American Fundamentalism Since 1850. Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University (Unusual Publications). ISBN 0-89084-350-3.

- Bebbington, David Westward. (1990). "Baptists and Fundamentalists in Inter-War United kingdom." In Keith Robbins, ed. Protestant Evangelicalism: Uk, Republic of ireland, Germany and America c.1750-c.1950. Studies in Church History subsidia 7, 297–326. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 0-631-17818-10.

- Bebbington, David W. (1993). "Martyrs for the Truth: Fundamentalists in Uk." In Diana Wood, ed. Martyrs and Martyrologies, Studies in Church History Vol. xxx, 417–451. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 0-631-18868-1.

- Barr, James (1977). Fundamentalism. London: SCM Press. ISBN 0-334-00503-five.

- Caplan, Lionel (1987). Studies in Religious Fundamentalism. London: The MacMillan Printing, ISBN 0-88706-518-X.

- Carpenter, Joel A. (1999). Revive Us Once more: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-nineteen-512907-5.

- Cole, Stewart Grant (1931). The History of Fundamentalism, Greenwood Press ISBN 0-8371-5683-1.

- Doner, Colonel V. (2012). Christian Jihad: Neo-Fundamentalists and the Polarization of America, Samizdat Creative

- Elliott, David R. (1993). "Knowing No Borders: Canadian Contributions to Fundamentalism." In George A. Rawlyk and Marker A. Noll, eds. Amazing Grace: Evangelicalism in Australia, United kingdom, Canada and the United States. Grand Rapids: Bakery. 349–374, ISBN 0-7735-1214-4.

- Dollar, George W. (1973). A History of Fundamentalism in America. Greenville: Bob Jones Academy Press.

- Hankins, Barry. (2008). American Evangelicals: A Contemporary History of A Mainstream Religious Movement, scholarly history excerpt and text search

- Harris, Harriet A. (1998). Fundamentalism and Evangelicals. Oxford University. ISBN 0-nineteen-826960-9.

- Hart, D. G. (1998). "The Necktie that Divides: Presbyterian Ecumenism, Fundamentalism and the History of Twentieth-Century American Protestantism". Westminster Theological Journal. 60: 85–107.

- Hughes, Richard Thomas (1988). The American quest for the primitive church 257pp excerpt and text search

- Laats, Adam (February. 2010). "Forging a Fundamentalist 'I Best System': Struggles over Curriculum and Educational Philosophy for Christian Day Schools, 1970–1989," History of Instruction Quarterly, fifty (February. 2010), 55–83.

- Longfield, Bradley J. (1991). The Presbyterian Controversy. New York: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN 0-nineteen-508674-0.

- Marsden, George M. (1995). "Fundamentalism equally an American Phenomenon." In D. Thousand. Hart, ed. Reckoning with the By, 303–321. Grand Rapids: Bakery.

- Marsden; George M. (1980). Fundamentalism and American Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-nineteen-502758-two; the standard scholarly history; excerpt and text search

- Marsden, George M. (1991). Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism excerpt and text search

- McCune, Rolland D (1998). "The Formation of New Evangelicalism (Office Ane): Historical and Theological Antecedents" (PDF). Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal. three: 3–34. Archived from the original on 10 September 2005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - McLachlan, Douglas R. (1993). Reclaiming Accurate Fundamentalism. Independence, Mo.: American Association of Christian Schools. ISBN 0-918407-02-8.

- Noll, Mark (1992). A History of Christianity in the The states and Canada.. K Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Visitor. 311–389. ISBN 0-8028-0651-ane.

- Noll, Mark A., David W. Bebbington and George A. Rawlyk eds. (1994). Evangelicalism: Comparative Studies of Pop Protestantism in North America, the British Isles and Across, 1700–1990.

- Rawlyk, George A., and Marker A. Noll, eds. (1993). Amazing Grace: Evangelicalism in Australia, Great britain, Canada, and the United States.

- Rennie, Ian Due south. (1994). "Fundamentalism and the Varieties of Northward Atlantic Evangelicalism." in Mark A. Noll, David W. Bebbington and George A. Rawlyk eds. Evangelicalism: Comparative Studies of Popular Protestantism in North America, the British Isles and Beyond, 1700–1990. New York: Oxford Academy Press. 333–364, ISBN 0-nineteen-508362-eight.

- Russell, C. Allyn (1976), Voices of American Fundamentalism: 7 Biographical Studies, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, ISBN0-664-20814-two

- Ruthven, Malise (2007). Fundamentalism: A Very Short Introduction excerpt and text search

- Sandeen, Ernest Robert (1970). The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, ISBN 0-226-73467-vi

- Seat, Leroy (2007). Fed Up with Fundamentalism: A Historical, Theological, and Personal Appraisal of Christian Fundamentalism. Liberty, MO: 4-50 Publications. ISBN 978-i-59526-859-4

- Small, Robyn (2004). A Delightful Inheritance (1st ed.). Wilsonton, Queensland: Robyn Pocket-size. ISBN978-1-920855-73-4.

- Stackhouse, John One thousand. (1993). Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century

- Trollinger, William V. (1991). God'due south Empire: William Bell Riley and Midwestern Fundamentalism excerpts and text search

- Utzinger, J. Michael (2006). Yet Saints Their Watch Are Keeping: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and the Evolution of Evangelical Ecclesiology, 1887–1937, Macon: Mercer University Press, ISBN 0-86554-902-8

- Witherup, S. South., Ronald, D. (2001). Biblical Fundamentalism: What Every Catholic Should Know, 101pp excerpt and text search

- Wood, Thomas E. et al. "Fundamentalism: What Function did the Fundamentalists Play in American Society of the 1920s?" in History in Dispute Vol. three: American Social and Political Movements, 1900-1945: Pursuit of Progress (Gale, 2000), 13pp online at Gale.

- Young, F. Lionel, Iii, (2005). "To the Correct of Baton Graham: John R. Rice's 1957 Cause Against New Evangelicalism and the Cease of the Fundamentalist-Evangelical Coalition." Th. M. Thesis, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

Primary sources [edit]

- Hankins, Barr, ed. (2008). Evangelicalism and Fundamentalism: A Documentary Reader extract and text search

- Torrey, R. A., Dixon, A. C., et al. (eds.) (1917). The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth partial version at web.archive.org. Accessed 2011-07-26.

- Trollinger, William Vance Jr., ed. (1995). The Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bong Riley. (Creationism in Twentieth-Century America: A Ten-Volume Anthology of Documents, 1903–1961. Vol. iv.) New York: Garland, 221 pp. excerpt and text search

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_fundamentalism

0 Response to "Evangelical Fundamentalist Born Again Christians"

Post a Comment